When Sen. Bernie Sanders and New York City Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani recently rallied with striking Starbucks workers, they trumpeted a “New York where every worker can live a life of decency.” Mr. Mamdani promised a $30 minimum wage in the name of dignity on the campaign trail. Their intentions might be noble; their logic isn’t. By artificially hiking entry-level wages through political mandates rather than skills, productivity or experience, they don’t lift up workers; they wall off the very on-ramp to mobility.

We know this firsthand. Neither of our first real jobs was glamorous. They were at McDonald’s in Iron Mountain, Michigan (Scott) and Kmart in Midland, Michigan (Dan). We started at fries and collecting carts, but gradually both moved up to drive-thru, cashier and managing people and closing shifts. Eventually, our responsibilities included inventory, scheduling, customer-service recoveries and profit margins. It was the best business education of our lives. Call it a ketchup-stained, “blue light special” MBA. We didn’t have elite networks, legacy connections or wealthy mentors. We had a crew uniform and accountability. McDonald’s and Kmart didn’t just teach us how to work — they taught us how to lead.

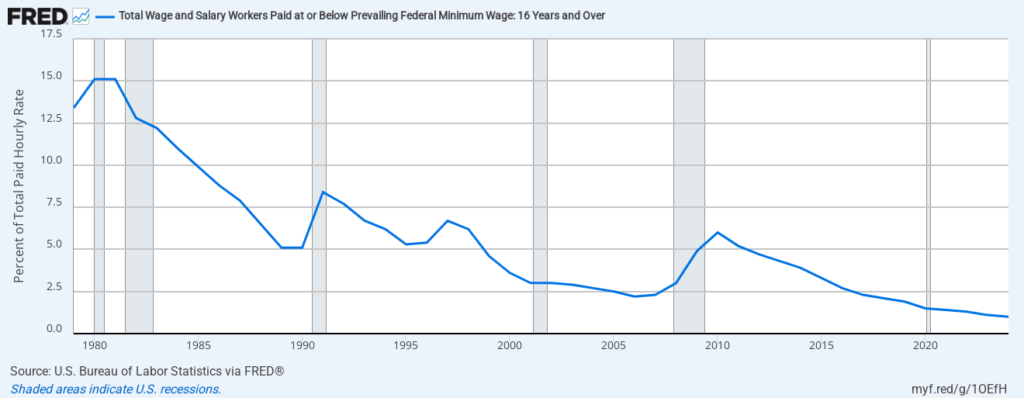

People sneer at “burger-flipping” and “cart-pushing” but many of America’s best managers, franchise owners and entrepreneurs cut their teeth behind those stainless-steel counters and carts. One in eight Americans has worked at McDonald’s at some point. Entry-level jobs are not “traps” that freeze workers in poverty. They are on-ramps: the place where inexperienced workers merge into the labor market and start accelerating. Even a glance at the numbers dispels the caricature. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only about one percent of hourly US workers — roughly 842,000 people — earn at or below the federal minimum wage. Nearly half are under 25. Most work part-time. Many are students or first-time entrants. These roles are training grounds, not endpoints. Teens in low-wage jobs tend to move to higher-paying ones. Wages tend to rise as productivity rises, not because lawmakers decree it.

In language everyone can understand: You don’t learn to merge onto the interstate by starting at highway speed. You start slowly, learn the feel of the wheel and build momentum. Raise the minimum speed of the on-ramp to 70, and a lot of young drivers will never get off the shoulder.

Politics cannot eliminate the realities of the labor market. If you force employers to pay $25 or $30 an hour for roles designed for inexperienced workers, businesses respond the only way they can: fewer openings, more automation, tighter hiring criteria and restricted hours. You don’t have to theorize about it; we’ve seen it. As David Neumark and William Wascher conclude in a paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, “A sizable majority of the studies surveyed in this monograph give a relatively consistent…indication of negative employment effects of minimum wages.”

Critics say this is “corporate propaganda” — that higher wages prevent exploitation. But this assumes employers are static and workers have no agency. It also assumes people come to the labor market perfectly prepared. They don’t. Some students arrive from failing K-12 systems. Some lack soft skills such as showing up on time, resolving conflict and taking directions. Some are single parents navigating childcare regulations that raise prices and push them out of the workforce. These barriers are real, and they explain far more worker stagnation than starting wages at Starbucks.

The irony is that a higher minimum wage doesn’t attack any of these root issues. Instead, it blocks the path to improvement. Think of it like a grading curve: if you can’t submit an essay until it’s already an A paper, many people will simply never write.

The McDonald’s and Kmart story described above isn’t rare; it’s American. The first job is rarely glamorous — but it teaches responsibility, teamwork and consequences. It shows you how to deal with angry customers, how to meet targets, how to win a promotion and even how to manage people. You learn that work is not punishment; it’s the means to your future.

If lawmakers want to improve income mobility for young and low-income Americans, they should tackle the real bottlenecks: dysfunctional schools, needless occupational licensing (hair braiding and floristry should not require bureaucratic rituals) and childcare regulations that price parents out of the job market. Those reforms widen the on-ramp. Wage floors barricade it.

America’s economic ladder is sturdy at the bottom, not because entry-level work pays extraordinarily well, but because it opens doors to a lifetime of skill acquisition and upward movement. The Golden Arches and Kmart didn’t just give us money. They gave us momentum. Don’t deny that opportunity to the next generation.